Why must we all work long hours to earn the right to live? Why must only the wealthy have access to leisure, aesthetic pleasure, self-actualization…? Everyone seems to have an answer, according to their political or theological bent. One economic bogeyman, so-called “trickle-down” economics, or “Reaganomics,” actually predates our 40th president by a few hundred years at least. The notion that we must better ourselves—or simply survive—by toiling to increase the wealth and property of already wealthy men was perhaps first comprehensively articulated in the 18th-century doctrine of “improvement.” In order to justify privatizing common land and forcing the peasantry into jobbing for them, English landlords attempted to show in treatise after treatise that 1) the peasants were lazy, immoral, and unproductive, and 2) they were better off working for others. As a corollary, most argued that landowners should be given the utmost social and political privilege so that their largesse could benefit everyone.

This scheme necessitated a complete redefinition of what it meant to work. In his study, The English Village Community and the Enclosure Movements, historian W.E. Tate quotes from several of the “improvement” treatises, many written by Puritans who argued that “the poor are of two classes, the industrious poor who are content to work for their betters, and the idle poor who prefer to work for themselves.” Tate’s summation perfectly articulates the early modern redefinition of “work” as the creation of profit for owners. Such work is virtuous, “industrious,” and leads to contentment. Other kinds of work, leisurely, domestic, pleasurable, subsistence, or otherwise, qualifies—in an Orwellian turn of phrase—as “idleness.” (We hear echoes of this rhetoric in the language of “deserving” and “undeserving” poor.) It was this language, and its legal and social repercussions, that Max Weber later documented in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Karl Marx reacted to in Das Capital, and feminists have shown to be a consolidation of patriarchal power and further exclusion of women from economic participation.

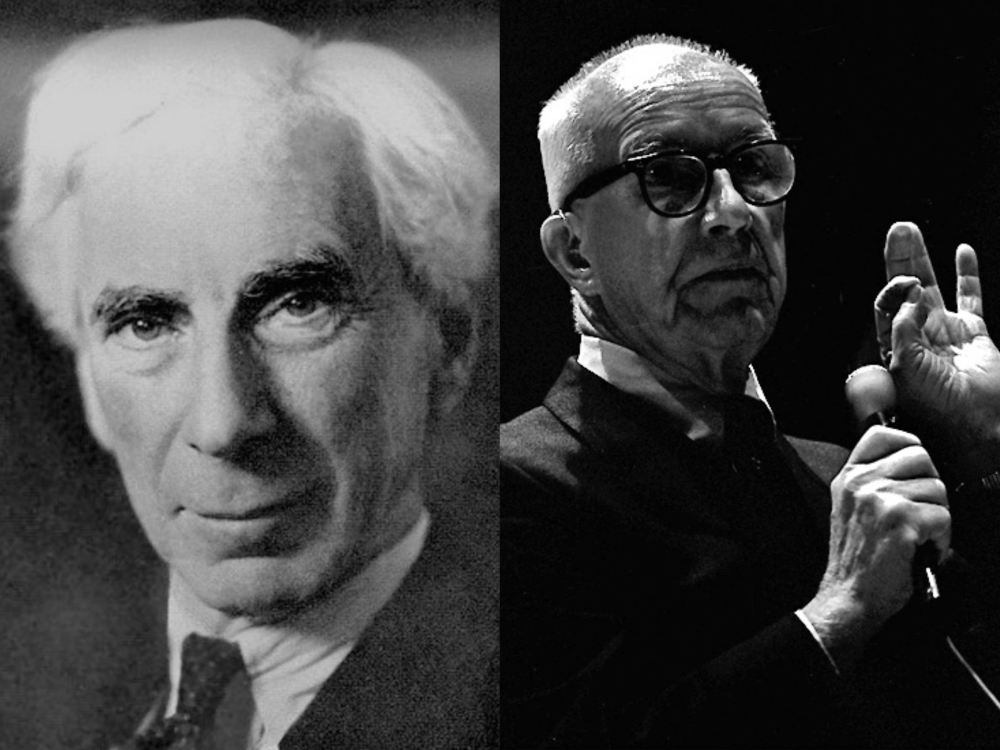

Along with Marx, various others have raised significant objections to Protestant, capitalist definitions of work, including Thomas Paine, the Fabians, agrarians, and anarchists. In the twentieth century, we can add two significant names to an already distinguished list of dissenters: Buckminster Fuller and Bertrand Russell. Both challenged the notion that we must have wage-earning jobs in order to live, and that we are not entitled to indulge our passions and interests unless we do so for monetary profit or have independent wealth. In a New York Times column on Russell’s 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness,” Gary Gutting writes, “For most of us, a paying job is still utterly essential — as masses of unemployed people know all too well. But in our economic system, most of us inevitably see our work as a means to something else: it makes a living, but it doesn’t make a life.”

In far too many cases in fact, the work we must do to survive robs us of the ability to live by ruining our health, consuming all our precious time, and degrading our environment. In his essay, Russell argued that “there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what has always been preached.” His “arguments for laziness,” as he called them, begin with definitions of what we mean by “work,” which might be characterized as the difference between labor and management:

What is work? Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid.

Russell further divides the second category into “those who give orders” and “those who give advice as to what orders should be given.” This latter kind of work, he says, “is called politics,” and requires no real “knowledge of the subjects as to which advice is given,” but only the ability to manipulate: “the art of persuasive speaking and writing, i.e. of advertising.” Russell then discusses a “third class of men” at the top, “more respected than either of the classes of the workers”—the landowners, who “are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work.” The idleness of landowners, he writes, “is only rendered possible by the industry of others. Indeed their desire for comfortable idleness is historically the source of the whole gospel of work. The last thing they have ever wished is that others should follow their example.”

The “gospel of work” Russell outlines is, he writes, “the morality of the Slave State,” and the kinds of murderous toil that developed under its rule—actual chattel slavery, fifteen hour workdays in abominable conditions, child labor—has been “disastrous.” Work looks very different today than it did even in Russell’s time, but even in modernity, when labor movements have managed to gather some increasingly precarious amount of social security and leisure time for working people, the amount of work forced upon the majority of us is unnecessary for human thriving and in fact counter to it—the result of a still-successful capitalist propaganda campaign: if we aren’t laboring for wages to increase the profits of others, the logic still dictates, we will fall to sloth and vice and fail to earn our keep. “Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do,” goes the Protestant proverb Russell quotes at the beginning of his essay. On the contrary, he concludes,

…in a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day, every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving, however excellent his pictures may be. Young writers will not be obliged to draw attention to themselves by sensational pot-boilers, with a view to acquiring the economic independence for monumental works, for which, when the time at last comes, they will have lost the taste and capacity.

The less we are forced to labor, the more we can do good work in our idleness, and we can all labor less, Russell argues, because “modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all” instead of “overwork for some and starvation for others.”

A few decades later, visionary architect, inventor, and theorist Buckminster Fuller would make exactly the same argument, in similar terms, against the “specious notion that everybody has to earn a living.” Fuller articulated his ideas on work and non-work throughout his long career. He put them most succinctly in a 1970 New York magazine “Environmental Teach-In”:

It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest…. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian-Darwinian theory, he must justify his right to exist.

Many people are paid very little to do backbreaking labor; many others paid quite a lot to do very little. The creation of surplus jobs leads to redundancy, inefficiency, and the bureaucratic waste we hear so many politicians rail against: “we have inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors”—all to satisfy a dubious moral imperative and to make a small number of rich people even richer.

What should we do instead? We should continue our education, and do what we please, Fuller argues: “The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.” We should all, in other words, work for ourselves, performing the kind of labor we deem necessary for our quality of life and our social arrangements, rather than the kinds of labor dictated to us by governments, landowners, and corporate executives. And we can all do so, Fuller thought, and all flourish similarly. Fuller called the technological and evolutionary advancement that enables us to do more with less “euphemeralization.” In Critical Path, a visionary work on human development, he claimed “It is now possible to give every man, woman and child on Earth a standard of living comparable to that of a modern-day billionaire.”

Sound utopian? Perhaps. But Fuller’s far-reaching path out of reliance on fossil fuels and into a sustainable future has never been tried, for some depressingly obvious reasons and some less obvious. Neither Russell nor Fuller argued for the abolition—or inevitable self-destruction—of capitalism and the rise of a workers’ paradise. (Russell gave up his early enthusiasm for communism.) Neither does Gary Gutting, a philosophy professor at the University of Notre Dame, who in his New York Times commentary on Russell asserts that “Capitalism, with its devotion to profit, is not in itself evil.” Most Marxists on the other hand would argue that devotion to profit can never be benign. But there are many middle ways between state communism and our current religious devotion to supply-side capitalism, such as robust democratic socialism or a basic income guarantee. In any case, what most dissenters against modern notions of work share in common is the conviction that education should produce critical thinkers and self-directed individuals, and not, as Gutting puts it, “be primarily for training workers or consumers”—and that doing work we love for the sake of our own personal fulfillment should not be the exclusive preserve of a propertied leisure class.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Brian Eno’s Advice for Those Who Want to Do Their Best Creative Work: Don’t Get a Job

Hear Alan Watts’s 1960s Prediction That Automation Will Necessitate a Universal Basic Income

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness